The Biology of Blackwater

Before you ask, yes, that seahorse has an octopus on its head.

If you have ever jumped into the open ocean at night and wondered, "What the heck was that?" you are at the right place. As often as we can, I team up with Kona Honu Divers to travel a few miles straight out of Waianae, Oahu at night with dive gear. We have seen a different spattering of life on every dive, so this page will be updated as we come across more alien life forms.

How alien? For starters, most of these animals exhibit some form of biolumination making the nocturnal pelagic world glow. Because most of these critters spend their days deeper than light can appreciably penetrate and come to the surface only at night, they need to produce their own light to find and identify one another. Many of these animals can be identified to species based on the patterns of photophores alone. Of course, making your presence known in an ocean full of predators can be hazardous.

In a world devoid of stuff to hide behind, pelagic inhabitants have devised a number of adaptations to avoid detection. Counter shading, or having a dark dorsal surface and light underside, is common in many larger pelagic animals. Smaller fishes and cephalopods have combined this with biolumination on the underside in an adaptation termed counterillumination. Some squid and lanternfishes have even been shown to vary the brightness of their ventral photophores to mimic the brightness of the moon. Many fishes combine counterillumination with highly reflective surfaces that reflect the ambient shade of blue back at any would-be predators.

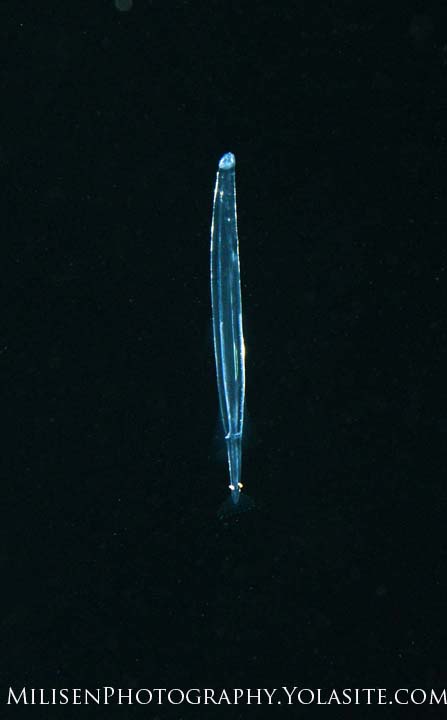

Larval flounder (Chascanopsetta prorigera)

A more common form of camouflage, especially among invertebrates, is the use of gelatin to make yourself nearly transparent. Such animals are very hard to study since they are not counted by optical counting apparatus and the gelatin is quickly destroyed by net tows. Thus, very little is known about many of these highly abundant and ecologically important animals.

Below you will find a basic ID guide with the animals I have encountered so far while out in pelagic waters. They have been categorized with the holoplankton (permanent members of the plankton) at the top and meroplankton (organisms that spend only part of their life as plankton) at the bottom.

Callistoctopus sp.

Holoplankton

Winged Box Jelly

Alatina alata

The winged box jelly is best known for the excruciating sting produced by its tentacles. This typically pelagic species terrorizes Hawaiian beachgoers 7-10 days after the full moon when it heads inshore to spawn.

Chaetognath

Chaetognaths are one of the most common organisms observed during pelagic night dives. Otherwise known as arrow worms, they tend to be only two or four centimeters long and highly transparent. If you watch carefully, they often utilize dive lights to capture food.

Ctenophore

Beroe sp.

This ctenophore has a large hollow space that serves to digest its prey. Its mouth is able to take primitive bites out of other gelatinous organisms. It seems to have a special liking for other ctenophores. It can resemble a swimming sac.

Ctenophore

Bolinopsis

One of the more common ctenophores, Bolinopsis evades detection by having an almost perfectly clear body. While feeding on its prey of zooplankton, it will orient itself vertically in the water column.

Ctenophore

Leucothea

This family is contains some of the largest ctenophores on earth at 25 cm in length! These jellies tend to orient themselves horizontally when feeding. Look for a body covered in papillae, canals on the two oral lobes and a pair of trailing tentacles.

Flying Fish

Exocoetidae

This readily recognizable visitor is encountered more frequently on the ride out to the site where it can be seen leaping from the surface and gliding on its elongated pectoral fins for dozens of meters.

Heteropod

Commonly known as heteropods, these little wonders propel themselves gracefully with the use of a dorsal fin of sorts which is more like a modified snail foot. Their bodies can be classified into three parts: the proboscis, trunk and tail regions. If you look closely, you can also often make out eye spots and a remnant of the shell.

Young Mahi Mahi

Coryphaena hippurus

It is hard to believe that at about 1 cm long this little tyke will be one of the most sought after game fish in the ocean. Mahi this young grow very fast. In a year, this animal may be almost a meter long! To do this, they eat immense amounts of food multiple times per day. Like the larger adults, young mahi are usually seen hugging the surface associated with some kind of flotsam.

Polychaete Worm

Otherwise known as bristleworms, many of these squiggly critters have the potential to leave painful spines behind in any skin they might contact.

Pyrosome

Like salps, pyrosomes are a type of colonial tunicate. They move with the coordinated beating of cilia in each individual zooid, moving water from the outside of the tube to the inside that then exits from the one opening in the colony. They are unusually bioluminescent and one of the more obvious organisms seen on blackwater dives. Look for symbiotic shrimp on the inside of the colony.

Hippocampus fisheri

Pelagic seahorses are a rare treat. They look and act much like seahorses with young developing inside the father's characteristic pound. Unlike normal seahorses, however, these are free swimming animals that migrate vertically like many other mesopelagic organisms. Look for them cruising just under the water's surface. Click here for more pics

Salps can occur as either solitary (oozoid) or colonial (blastozooid) organisms. The oozoid reproduces asexually into a chain of sequential hermaphroditic blastozooids that then separate to sexually produce more oozoids. Being chordates, they have a central notochord and are structurally much closer to vertebrates than other invertebrates we might encounter. Click here for more images.

Crowned jelly

Cephea cephea

They may look pretty, but many members of this class and the related hydrozoans can pack a whallop with stinging tentacles. Best viewed from a short distance.

Siphonophore

Agalma okeni

Siphonophores may look superficially like a single organism when in fact they are a free swimming colony of them. They drift planktonically with tentacle-like structures splayed out in a web of stinging cells to capture the small pelagic animals that comprise its prey. When disturbed, the siphonophores we see quickly reel in their webs and move remarkably fast.

Larval banded coral shrimp

Stenopus hispidis

The shrimps we see belong to any one of a number of taxonomic groups including euphasids (krill-like), mysids, luciferidae, caridea, and pennaeidae. In common-speak, they span the gamut from krill to the white shrimp you eat to tiny shrimp you might hardly notice.

Thecosome

Clio pyramidata

Clio pyramidata is a species of shelled, pelagic gastropod that is commonly seen on our night dives. They feed passively using a mucous net to snare microalgae. Thecosomes represent an especially important part of the food web of the Southern Ocean. Their delicate, calcareous shells are very susceptible to degradation by ocean acidification.

Juvenile paper nautilus

Argonauta sp.

This is a young pelagic octopus that commonly hitches rides on salp blastozooid chains. They blend in rather well with the orange organs on the salps, so you have to look for irregularities in the patterns on the salp chains to find them.

Meroplankton

Larval Fish-Blenny

Developing fish will often take to the sea to escape the more common reef predators. Once their development is complete, they wait for a cue, often a chemical present in near shore habitats, to settle on the reef. The most common larval fish we see are blennies.

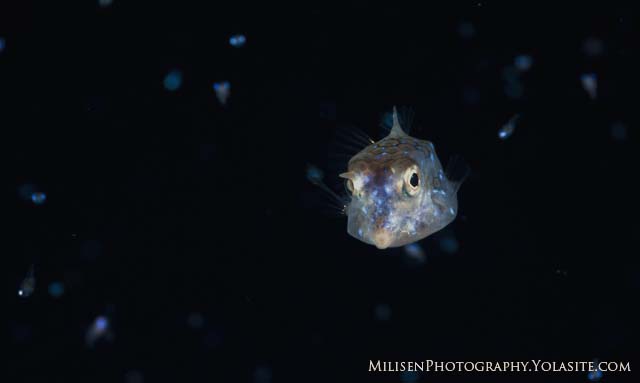

Juvenile Cowfish

Lactoria fornasini

This heart-warmer is infrequently encountered near shore hugging the bottom. They use their dorsal and anal fins in a sculling motion to move about, making them look like little tanks.

Larval Flounder

Bothus mancus

Juvenile flounder are sometimes encountered near the surface at night. These swimming windowpanes are enthralling partly because they are so strange, partly because they are so recognizable, and partly because you can see nearly every organ and bone in their body. Unlike adults, young flounder start off life with eyes on opposite sides of their heads like normal fish. Eventually, one of the eyes migrates over to the other side of the head. Which side of the head has the eyes helps determine what species the fish is.

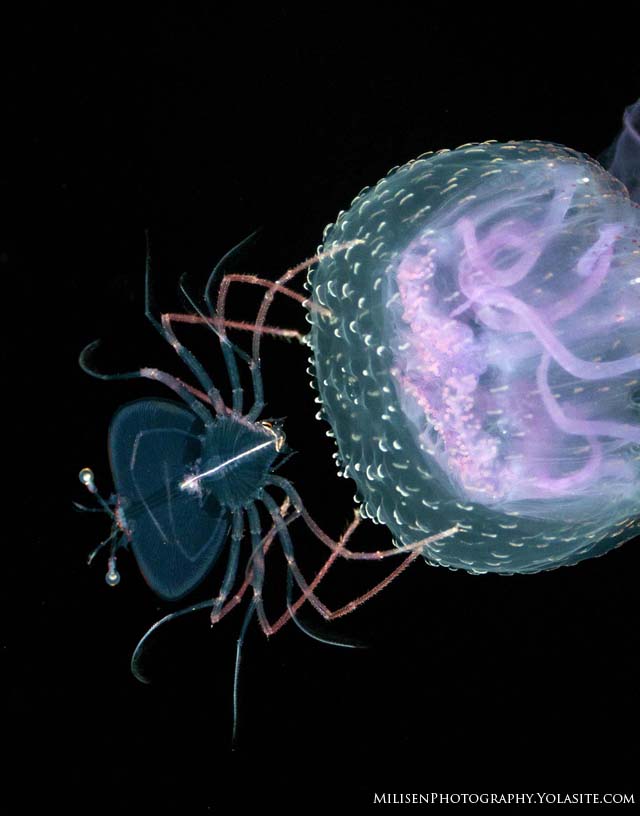

Lobster Phyllosoma

Some lobsters start off life as a smaller lobster. Most, however, start off looking more like a window pane. This larval stage is the defining characteristic of lobsters in the infraorder Acheleta. Phylosoma eat gelatinous plankton and can be observed dragging their victims around. The phyllosoma at right has a scyphozoan Pelagia noctiluca in its clutches, but they will readily eat siphonophores as well.

Crab Megalops Larva

Crabs develop through two life phases (zooea and megalops) in the pelagios before settling in the adult form we know best.