This is a modified version of an article that appeared in issue 21 of Shark Diver Magazine

I was making plans to travel to Kona on the hunt for Hawaii’s elusive hammerheads. Over the phone, my friend said excitedly, “While you’re here, we can do a black-water dive. It’s like a blue water dive, but at night!” A late night break from a weekend of diving to do some more…um…diving sounded like a good idea to me. I told him to sign me up immediately.

Two weeks later, my friends and I hung precariously under the boat. We were about 2 miles off the coast of Kona. Beneath us lay 3000 feet of water the color of used motor oil. Eerie, gelatinous beings drifted slowly by. We were watching the largest migration on earth. Every night, billions of mesopelagic organisms make a migration from their deep-water haunts towards the surface to feed. These critters are so dense that they form a zone known as the deep scattering layer where sonar cannot penetrate. Dominant life forms include ctenophores, cephalopods, and larval reef species such as fish and crustaceans. Unlike reef diving where the creatures, large and small, exist within a colorful backdrop, the life in the nocturnal pelagios is presented against infinitesimal nothingness. Big Island Divers sold it as the closest you can get to outer space on the face of the earth, and while I have since done many pelagic night dives since, at the time I found it to be stranger than described. See my article on Oahu blackwater diving for more info.

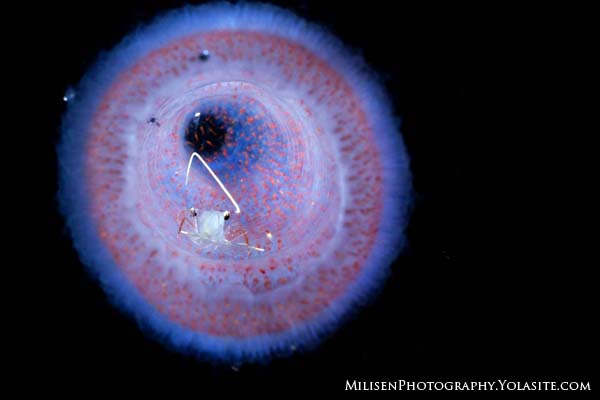

Pyrosoma atlanticum with commensal shrimp

Megalops stage crab larva pre-settlement

At night, everything glows. The ctenophores’ cilia oscillate with inferences of reds and purples. Colonies of salps look like long strings of tiny Christmas lights. Deep-sea anglerfish use glowing lures to attract prey to their mouths, while lanternfish species can even be identified by the pattern and color of illumination on their bodies.

And then there was the strange olive-green fish that went streaking through our group at a high speed. I looked over at my buddies. When one of them signaled for “shark,” I assumed something ominous was chasing that fish through our dive group. As you might imagine, these dives are known for attracting tough customers including the occasional oceanic whitetip. Earlier that same day while diving the reef, I watched three huge ulua blow out of a cave past me while completely missing the two large hammerheads that cruised right over my head. I had no intention of missing a second unique sharky encounter. As the funny looking fish with the huge shiny eye and tiny pectoral fins disappeared into the dark, I wasn’t thinking about its exotic feeding techniques or those poor dolphins swimming around with holes in their sides. I was still wondering where the big shark was.

Cookie cutter shark (Isistius brasiliensis)

The odd fish was a rarely seen species of deep-water shark known as a cookie cutter shark (Isistius brasiliensis). During the day, the cookie cutter shark resides in the mesopelagic zone, just out of reach of light. At night, they follow the planktonic migration to the surface. These nightly migrations bring the cookie cutter into contact with long line fishermen who occasionally hook the small sharks. It almost never sees sunlight, so it must produce its own through luminescent organs that run along its belly, giving the shark a glowing olive-green hue. These light organs may also be used as a lure, bringing its fast-swimming prey within easy reach.

Unlike most other sharks that kill a prey item before devouring it, cookie cutter sharks lead parasitic lives, attaching to the sides of larger prey and gouging out golfball sized chunks of flesh with their powerful jaws and unique dental structure. The resulting scars are very distinctive and can be found in the sides of everything from billfish, tuna, cetaceans, and even larger sharks. They have also been known to attack submarines, leaving telltale crater wounds on their rubber sonar domes. The only recorded attack on humans is a report of a body that was found with two cookie cutter wounds in its side. Whether these were made pre or post mortem could not be determined.

It returned a minute later and from a completely different direction. This time I recognized it immediately, and this time it was on a mission. Like a torpedo, it rocketed through our group directly at the back of my buddy whose attention was focused on another floating jello-mold. We all watched the approach with apprehension. None of us alerted Gavin to his impending back pain; instead we all reached for our cameras. Even his mom, who was watching the whole event occur, was too busy taking video to get Gavin’s attention. Lucky for Gavin, the shark hesitated about a foot away from his wetsuit before abruptly changing tactics and swimming around him.

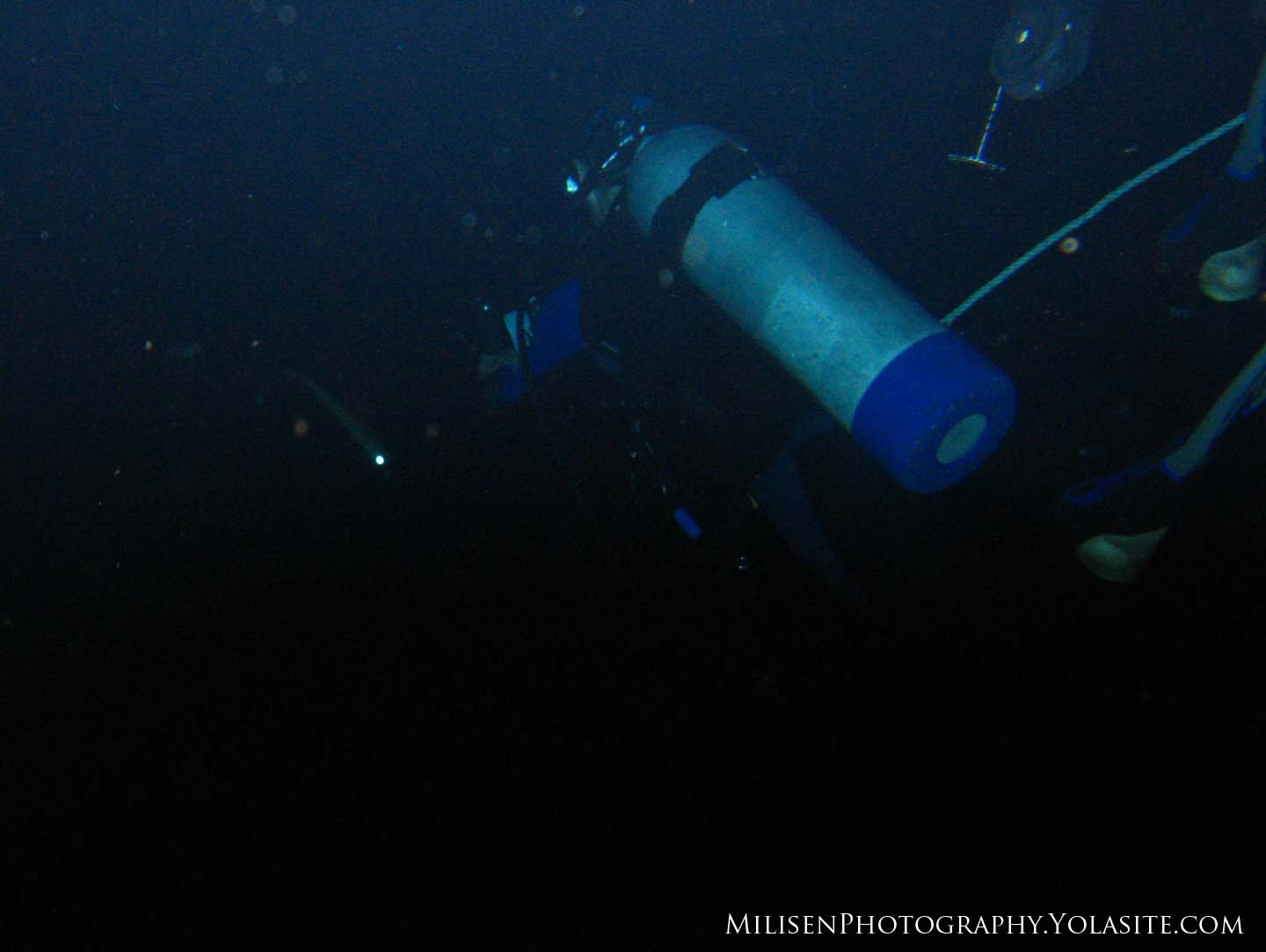

The shark hung around for a minute after that encounter, seeming as curious about us as we were about it. It made another, less threatening pass through our group and even swam through the divemaster’s arms. The rest of the dive continued to produce alien creatures from deep beneath the ocean’s surface, but at the end of the dive, the real showstopper was the cookie cutter shark. Back on the boat, Gavin cursed his missed opportunity to become the first living human exhibiting a crater wound. That’s just the kind of guy he is. Out of over 600 black-water dives this company has conducted, they have encountered cookie cutter sharks only two other times. The majority of people who have ever seen a cookie cutter shark in situ were the 8 of us on the boat that night. Maybe next time I’ll find my hammerheads.

Divemaster Josh Lambus and the Cookie Cutter Shark

The shark hung around for a minute after that encounter, seeming as curious about us as we were about it. It made another, less threatening pass through our group and even swam through the divemaster’s arms. The rest of the dive continued to produce alien creatures from deep beneath the ocean’s surface, but at the end of the dive, the real showstopper was the cookie cutter shark. Back on the boat, Gavin cursed his missed opportunity to become the first living human exhibiting a crater wound. That’s just the kind of guy he is. Out of over 600 black-water dives this company has conducted, they have encountered cookie cutter sharks only two other times. The majority of people who have ever seen a cookie cutter shark in situ were the 8 of us on the boat that night. Maybe next time I’ll find my hammerheads.